Orchid Conservation and Uses

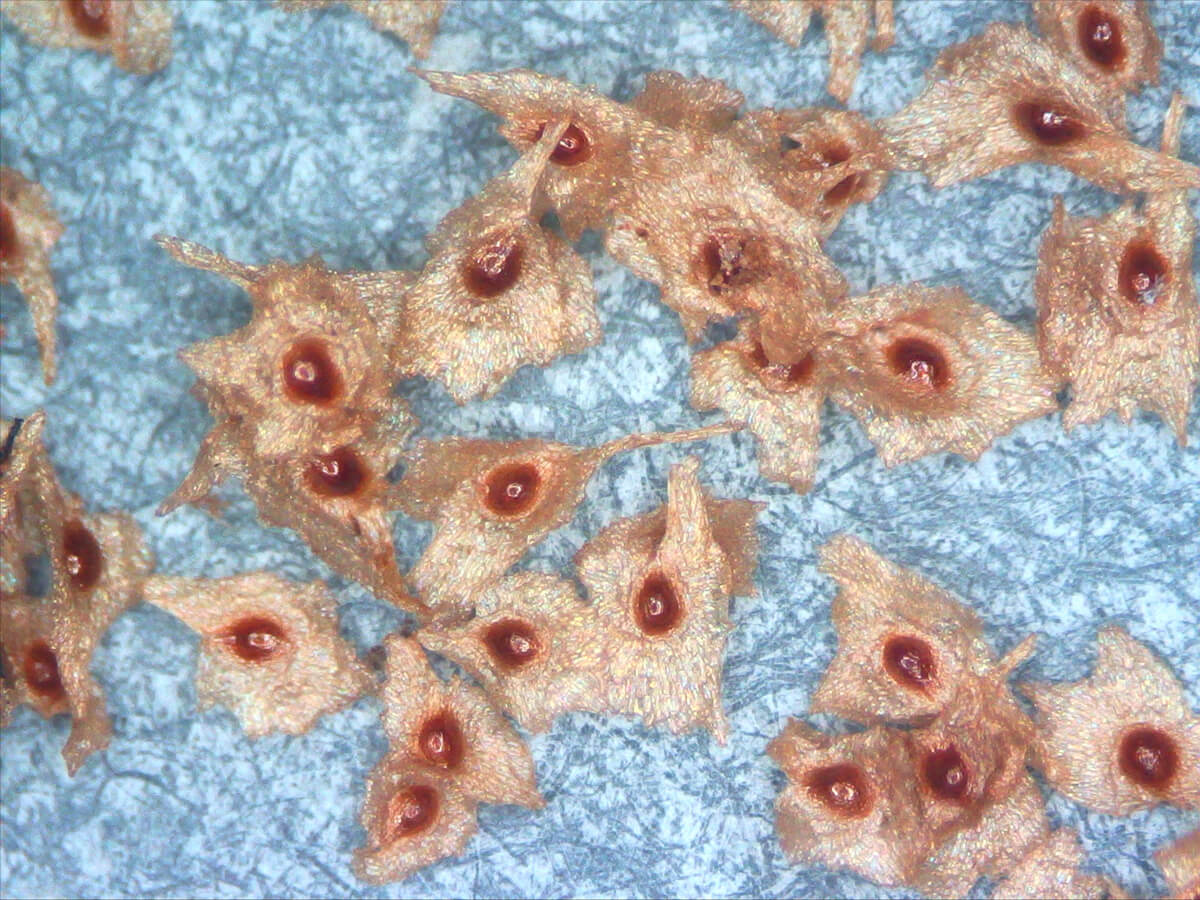

Orchidaceae is a large family of flowering plants estimated to include more than 25,000 species. Compared with most flowering plants, orchids have many special features in terms of morphology, structures, reproduction, and development. For example, their highly specialized tepals – eye-catching labella (specialized petals) attract specific pollinators. Instead of separate pistils and stamens, orchids have a combined reproductive organ, the column. Pollen is gathered into masses called pollinia. When an orchid is pollinated and fruits, the fruit releases thousands of tiny seeds when ripe. Viewing their anatomical structure, it can be seen that mature orchid seeds contain only a simple embryo (which only develops to the globular stage) covered in a thin seed coat without endosperm. In the wild, you can identify members of the orchid family based on the above-mentioned characteristics.

In this online exhibition are presented living orchids in the collection of the National Museum of Natural Science’s Botanical Garden and relevant research. In addition, the unique morphologies of orchid seeds, the use of tissue culture technology in the conservation of endangered orchid species, and the development of ornamental varieites are introduced. Moreover, some orchid species are valuable medicinal materials (such as Gastrodia elata and Anoectochilus roxburghii) and natural flavorings (such as the vanilla orchid (Vanilla planifolia)). In comparison to herbarium specimens, living collections can be damaged or destroyed due to natural disaster or by pests or disease. Thefore, the collection and preservation of living plants require more manpower and funds.

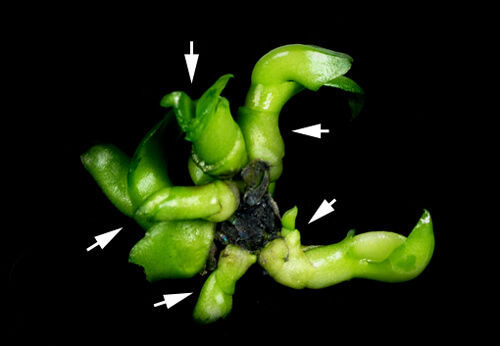

Orchid seed capsules can contain thousands of seeds. Charles Darwin was fascinated by orchids. When observing the seeds inside the orchid seed capsules, he wrote that if all the seeds in a capsule germinate and grow successfully, in just a few generations, a single orchid would “clothe with one uniform green carpet the entire surface of the land throughout the globe.” In actuality, this has not happened. Because orchid seeds are as fine as grains of sand or dust and do not possess endosperm, the embryo only develops to the globular stage, without differentiation of plumule or radicle. In the wild, once the capsule matures and cracks open, the seeds are scattered and most do not germinate. Only a few seeds that drift to a good environment where there are suitable mycorrhizal fungi are able to smoothly germinate and develop into protocorms. They then differentiate leaves and roots to grow into a complete plant. It was not until the 1920s that botanists discovered that many orchid seeds can germinate if provided inorganic mineral elements and soluble sugars (such as sucrose) under aseptic conditions. With advancements in aseptic propagation techniques, many tropical ornamental genera, such as Phalaenopsis, Dendrobium, and Cattleya, have been improved by horticultural breeders, who have produced beautiful and novel varieties. These outstanding plants can be commercially reproduced and propagated in large quantities through tissue culture techniques. Therefore, many beautiful orchids are no longer just for the wealthy to enjoy. They can be cultivated and appreciated by the general public.

Some orchids do not have chloryphyll. These are known as saprophytic orchids and include those in the genera Gastrodia, Galeola, and Lecanorchis. These orchids rely on mycorrhizal fungi to provide nutrients for completing their life cycle. This exhibition includes Gastrodia elata, which lives in symbiosis with wood-decomposing fungi of the genus Armillaria to enable their pseudobulbs to develop and grow smoothly. The symbiotic relationship between orchids and fungi has long been a topic of interest to botanists and an important part of orchid conservation efforts. To restore orchid populations, it is necessary to have suitable symbiotic fungi.