Larger Foraminifera

Foraminifera (forams for short) are (mostly) single-celled organisms (protists) with shell or test. Many have numerous small chambers inside. The name foraminifera is due to tiny pores in the many connecting channels between the chamber walls. They belong to the phylum Sarcomastigophora, class Granuloreticulosea, and order Foraminiferida. Adult foraminifera shells range in size from 0.02 millimeters to 22 centimeters and there are numerous shell types. In terms of internal structure, they can be very simple, such as with one chamber. Or, they can be composed of many chambers, with some having a well-developed and complicated stolon system for connecting the chambers. The shells are comprised of chitin, which includes tectine, calcium, and secreted protein-containing mucopolysaccharides for binding external particles, and is sandy and siliceous. Moreover, in recent years, some extant foraminifera without shells have been discovered in freshwater environments. Some foraminifera are encased in protoplasm, which is called a test and not a shell. This protoplasm is divided into ectoplasm and endoplasm. The former refers to the outer layer of the cytoplasm and can extend outward from one or more apertures on the test, forming a laterally connected network of pseudopodia for adhesion, movement, capture and transport of food particles, excretion of waste, gas exchange, and test construction. The endoplasm is the inner layer of the cytoplasm containing the nucleus and is where metabolism mainly takes place.

The foraminiferan fossil record dates back to the early Cambrian, coinciding with the appearance of the earliest skeletonized metazoans. Due to their large numbers, wide distribution, ease of fossilization and identification, and rapid evolution, foraminifera have long been very important microfossils for stratigraphic comparisons and study of paleoenvironmental changes. According to the World Foraminifera Database (http://www.marinespecies.org/foraminifera/), there are 8,970 extant species and 33,704 confirmed fossil species. Together, there are more than 42,200 species of foraminifera!

Living foraminifera are distributed across a wide range of habitats and environments, from the equator to the polar regions and from shallow seas to deep seas. They are even found in freshwater and moist rain forest soil. Moreover, foraminifera float, inhabit the surface or surface layers of sediment, attach to the surface of plants or algae, affix themselves to a hard substrate, and parasitize corals and other foraminifera by burrowing into them. According to the observations of extant species, some foraminifera are heterotropic protists that feed on organic detritus, bacteria, single-celled algae, other protists (including other foraminifera), and small eumetazoans (such as copepods). Some planktonic foraminifera live in the photic zone and some benthic foraminifera that inhabit shallow tropical seas host symbionts such as green algae, red algae, diatoms, and dinoflagellates. From another perspective, foraminifera are food sources for animals such as nematodes, polychaetes, mollusks, echinoderms, arthropods, and fish. They are also incidental food sources for deposit feeders and herbivores. Due to the large numbers of foraminifera, they play very important roles in the marine ecosystem trophic web.

Larger foraminifera (or large foraminifera) are not a formal classification. Rather, they are relatively large individuals (from several millimeters to 22 centimeters) that have complex internal structures (it is difficult to infer the internal arrangement of chambers or microstructures based on external appearance). Or, species identification can only be done by sectioning the shell. In the past, large foraminifera were also called complex foraminifera and higher foraminifera. Although there are large individuals (sometimes more than several millimeters), it is customary to classify those with simple internal structure (e.g., Dentalina which can reach a length of 1 centimeter) as small foraminifera. According to statistics provided by scholars, there are at least 156 genera of extant and fossil larger foraminifera (belonging to 26 families). Among the extant species of larger foraminifera, there are at least 30 genera (and at least 12 families).

Larger foraminifera are mainly distributed in warm, nutrient-poor tropical seas. Their large quantities of calcareous shells are an important source of biodetritus for filling in coral reef pores. However, they do not directly participate in the growth or construction of reefs. Some scholars have reported that in the early Eocene strata of southern France and northern Spain, a foramiferan reef has been found measuring 8 kilometers in length, 2 kilometers in width, and 5-10 meters in thickness, constructed by a single species of encrusting foraminifera (Solenomeris).

Based on a survey of sediment composition between coral reefs in the Great Barrier Reef, if calculated by dry weight, large foraminifera shells made up as much as 35%. If calculated by volume, the proportion of large foraminifera shells in Cenozoic limestone would be as high as 80%. From a 1997 survey of more than 120 coral reef areas around the world, the total amount of calcareous foraminifera shells is equivalent to an annual output of around 43 million tons of calcium carbonate, 80% of which is from large foraminifera with symbiotic algae. Therefore, large foraminifera can be said to significantly contribute to the long-term development of coral reefs.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Specimen photo captions: (with scale bar below each image)

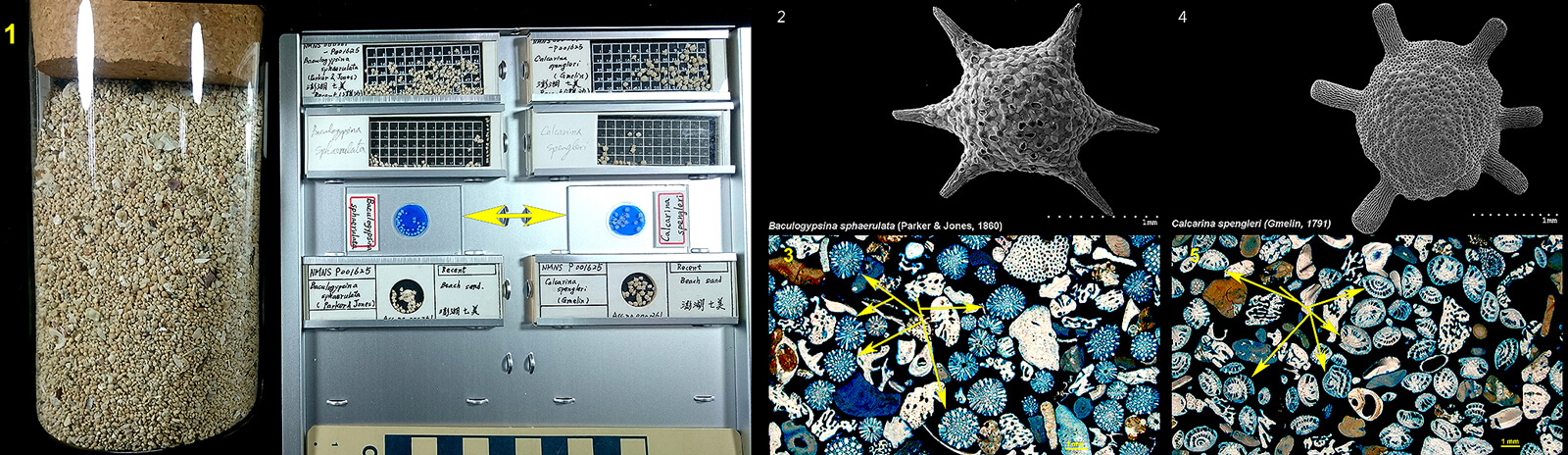

Figure 1 is of foraminferan sand from Penghu’s Qimei Island, as well as several types of selected large foraminifera. On two glass slides, epoxy resin and blue dye were used to bind foraminferan sand to produce thin translucent sections.

Figure 2 is a scanning electron microscope image of the calcareous shell of Baculogypsina sphaerulata. Figure 3 is a photo of a translucent section of beach sand. B. sphaerulata is indicated by the yellow arrows.

Figure 4 is a scanning electron microscope image of the calcareous shell of Calcarina spengleri. Figure 5 is a photo of a translucent section of beach sand. C. spengleri is indicated by the yellow arrows.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Scientific name: Baculogypsina sphaerulata (Parker & Jones)

Kingdom Protozoa

Phylum Sarcomastigophora

Class Granuloreticulosea

Order Foraminiferida

Family Calcarinidae

Baculogypsina

Genus Baculogypsina

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Scientific name: Calcarina spengleri (Gmelin)

Kingdom Protozoa

Phylum Sarcomastigophora

Class Granuloreticulosea

Order Foraminiferida

Family Calcarinidae

Genus Calcarina

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------