Algal Reef

Algal reefs are biotic reefs in which the main structure is of crustose coralline algae (also known as encrusting coralline algae), which bond together as they grow.

Coralline algae (or corallines) are named for the calcareous deposits contained within their cell walls, making the entire algal body hard. Hence, they are sometimes called “the coral of the plant world.” Generally, coralline algae can be divided into two major groups: geniculate corallines and nongeniculate corallines according to the development of non-calcifying algal nodes (genicules). The former can grow algal bodies that are pinnate, forked, or irregularly branched and affix to small plant bodies. Since calcification is limited to the internodes (intergenicules) of the algal body, and the nodes are made up of soft tissue without calcification, the entire algal body can sway with the current or waves. Nongeniculate corallines are almost completely calcified and are shell-like, lumpy, or dendritic in shape. They affix to hard substrates and are better able to resist wave action. In terms of taxonomy, all coralline algae belong to the phylum Rhodophyta and the subclass Corallinophycidae in the class Florideophycea. Among them, geniculate corallines belong to the family Corallinaceae in the order Corallinales and nongeniculate corallines belong to the orders Corallinales, Hapalidiales, and Sporolithales.

Crustose coralline algae, in addition to attaching and bonding to a substrate, in intermittent agitated soft substrate environments can attach to coral fragments, shell fragments, or gravel, and become rhodoliths. In Spain, France, Ireland, and Scotland, rhodoliths were traditionally used to condition the soil. Due to the calcareous deposits within crustose coralline algae, they can be substrates for attaching coral and shellfish larvae. Some coral larvae that undergo metamorphosis prefer certain species or genera of crustose coralline algae. Therefore, from multiple aspects, the growth of crustose coralline algae is beneficial to the development of coral reefs. In addition, in the face of increasing ocean acidification, some types of crustose coralline algae, especially Porolithon, which form algal ridges, convert the calcified magnesium calcite component into more stable dolomite, which can help to stabilize reef structure in the face of environmental changes.

Existing coralline algae are widely distributed from equatorial to polar seas. A small number of species can grow in brackish water and shallow seas with high levels of salinity. Depth distribution is from the intertidal zone to 268 meters. They are usually most abundant in shallow seas. In recent years, there have been reports of Pneophyllum cetinaensis (Žuljević et al., 2016), the only crustose coralline algae that can survive in freshwater environments, on pebbles, tree roots, and shells of adult river nerites (Theodoxus fluviatilis) along a total length of 75 kilometers, from the middle and lower reaches to the outlet (300-0 meters above sea level), of the Cetina River in Croatia.

For existing biotic reefs in tropical seas, in addition to providing large amounts of biodetritus, coralline algae are important organisms for stabilizing detrital substrates, strengthening reefs, and forming reef structures. Based on observations of the development and distribution of today’s reefs, nongeniculate corallines are often the main reef-building organisms in the intertidal zones and deeper waters (around 50 meters) where reef-building scleractinians do not grow well. For example, along coasts continuously impacted by high-energy currents or waves, only nongeniculate corallines can grow, forming a distinctive type of biotic reef – algal ridge. Around the atolls of small islands in the central Pacific and on windward coasts of small islands in the eastern and southwestern Caribbean, the development (more than 1 meter thick) of this type of algal reef results in good coastal barriers. In addition, on the eastern and western coasts of Central and South America and around the small islands of the Caribbean and Australia, algal reefs (1-5 meters thick) have been found on outer continental shelf and upper continental slope.

As some species of nongeniculate corallines can withstand harsh environmental conditions, such as low temperatures or high salinity, they can develop into large-scale reefs. For example, in the shallow waters near the polar regions of Norway are distributed large-scale algal reefs. In the high-salinity lagoon environment of Tunisia in the Mediterranean Sea (in summer: 45-51%, in winter 41-45%) is algal reef formed from nongeniculate corallines that stretches 31 kilometers. Moreover, on Waikiki Beach on Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands, surveys of algal reefs have shown that their formation is closely related to nutrients in the environment.

There have been very few reports on the “growth rate” (i.e., accretion rate) of algal reefs. According to the results of studies in the US Virgin Islands in the Caribbean, in the absence of grazing, the thickness of algal bodies increases at 1-5.2 millimeters/year and lateral growth rate is 0.9-2.3 millimeters/month. From surveys of coralline algae conducted along the coast of France, accretion rate is only 2-7 millimeters/year. However, in a single summer, it can increase 0.5-1 millimeters/month. In the presence of factors such as bioerosion, physical and chemical weathering, and later diagenesis, on a longer time scale the actual accretion rate of algal reefs should be much lower than the above observed results.

Based on research on extant algal reefs, they mainly develop in tropical and temperate shallow seas with high wave energy, low gnawing pressure, and high levels of nutrients. A small number develop in shallow seas that are extremely cold or that have high salinity. Of course, as reefs form, they are affected by factors such as bioerosion from bivalves, peanut worms, and boring sponges, diagenesis, undulation of ancient landforms, and relative rises in sea level.

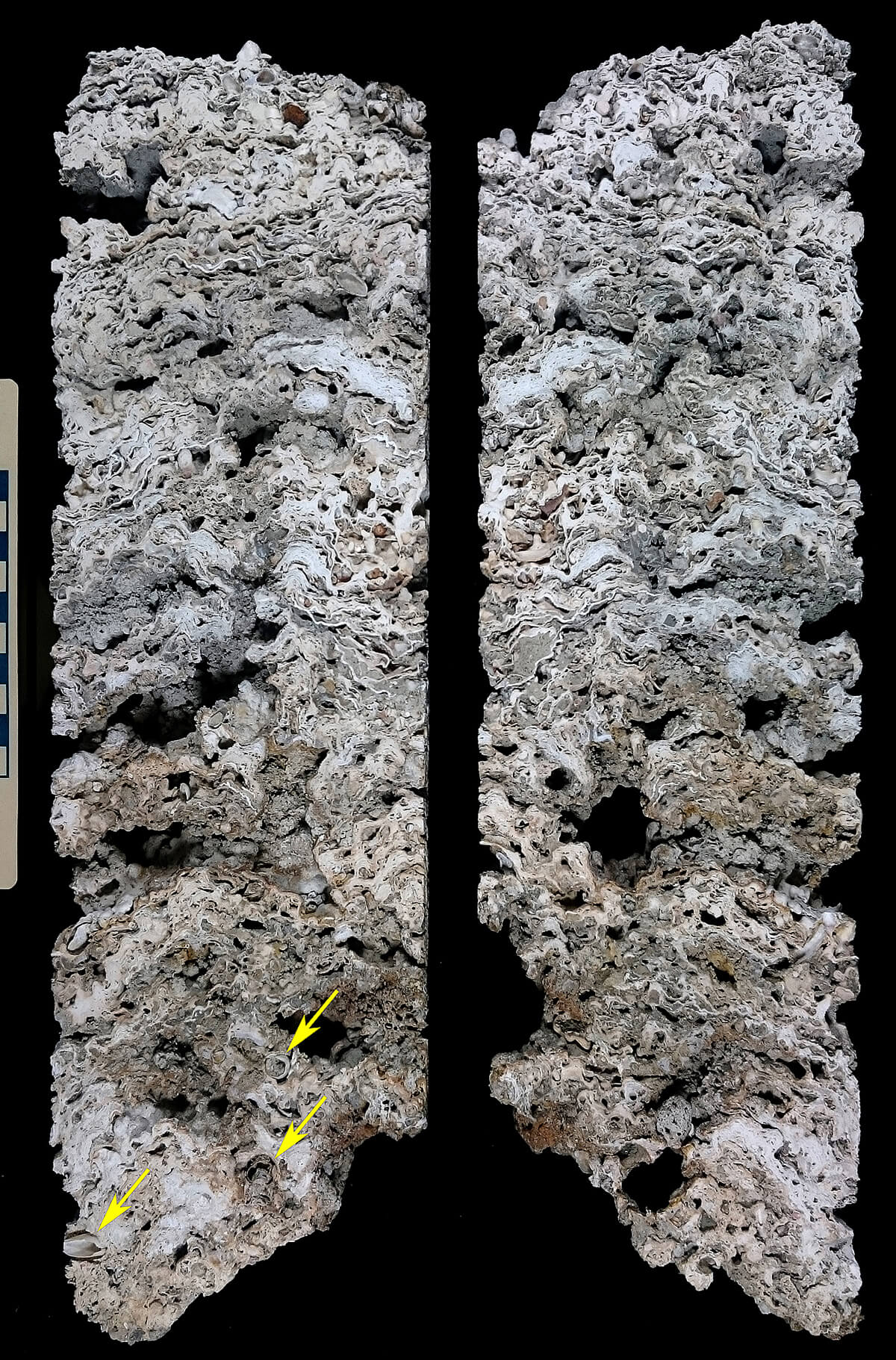

The exhibited specimen is a 5-inch core sample of limestone fragments from the Guanyin algal reef in Taoyuan City (1-centimeter scale bar). By cutting in half along the worn plane, perpendicular to the direction of growth and accretion, it is clear that this algal reef limestone was formed by layers of crustose coralline algae that grew and bonded. The reef pores were originally filled with unconsolidated clastic sediment and shells, which were cleared away during the cutting and polishing of the specimen. Therefore, what is seen is the original porous appearance of the reef. At the bottom of the photo on the left side of the cut specimen are several holes made by boring bivalves (indicated by the yellow arrows). According to field observations and geological drilling data, the biotic reef from where this sample was collected should be algal reef limestone with very little reef-building coral growth. Therefore, this core cut specimen shows a biotic reef with no local reef building coral growth.